The Physics of Strength Training

- Joe Parkinson

- Jun 8, 2020

- 4 min read

The Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science and Medicine defines strength as;

“The ability of a muscle to exert force and overcome a resistance.”

To better understand strength and strength training, you must first understand Newton’s second law of motion, commonly known as the law of acceleration. The law of acceleration states that when a body is acted on by a force, its resulting change in momentum takes place in the direction in which force is applied, is proportional to the force causing it, and is inversely proportional to its mass.

This relationship is expressed as;

F = m x a or Force = mass x acceleration.

Thus, a during a squat, the barbell moves in the direction of the line of action of the force being generated during concentric contraction of the working muscles, at a speed directly proportional to the force generated and inversely proportional to the mass of the barbell.

In this scenario, F is represented by the muscular contractions, M is represented by the mass of the barbell and A is represented by the speed at which the barbell is moving.

Understanding the law of acceleration better allows us to understand the force-velocity curve.

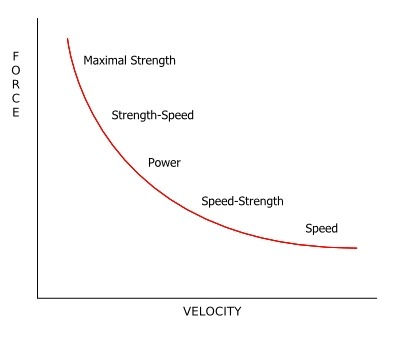

The force velocity curve shows the relationship between tension and the velocity of shortening or lengthening of the muscle. If training loads are high, movement velocity produced by a concentric muscle contraction is low and the training effect is primarily to increase strength. If the movement velocity is high, and the load is low, the main training effect is to improve speed.

Understanding the force velocity curve will allow for better training prescription and exercise selection for the athlete that you are working with and the training effects that you are trying to elicit.

Zatsiorsky & Kraemer (2006) suggest that the trade-off between force and velocity is thought to occur due to a decrease in the time available for muscular contraction. More time equals greater contractile force. Slower velocity exercises allow an athlete to develop more force and higher velocity exercises result in lower force production. Therefore, different exercises and intensities have been categorised into various segments on the force-velocity curve.

Maximum Strength

Williams et al., (2017) define Maximal strength as the ability to produce a maximal voluntary muscular contraction against an external resistance, and emphasise that it is commonly assessed by performing a 1-repetition maximum (1RM) during a dynamic exercise (squat, bench press, deadlift etc.). This training zone is typically classified by using intensities of approximately >90% of 1RM.

Strength-Speed

Strength-speed requires athletes to move less weight than when training for maximum strength, however, move it at a faster velocity (Verkhoshansky & Verkhoshansky, 2011). The strength-speed zone requires an athlete to produce optimal force in a shorter timeframe than the maximal strength zone. Relatively high intensities are used within this zone (80-90% of 1RM).

Power

Defined by the Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science and Medicine as the rate at which energy is expended or work is done (power = work done/time taken). The amount of power generated by an athlete is dependent on speed and strength, Speed x Strength = Power. A powerful athlete is able to transform energy into force at a fast rate. Power sits in the middle of strength-speed and speed-strength, producing the optimal amount force in the shortest time timeframe possible. Typically loads of 30-80% of 1RM are used.

Speed-Strength

Kurz (2001) suggests that speed-strength is the result of dividing an athlete’s maximal strength value in a given movement by the time it takes to reach that value (Tidow, 1990). It is the athlete’s ability to exert maximal force during high speed movement (Allerheiligen, 1994). As relatively high velocities are used within this zone (30-60% of 1RM), it leans more towards speed rather than strength – hence the ‘speed’-strength.

Speed

Defined by the Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science and Medicine as the the ability to perform a movement quickly. Speed is simply the maximum movement velocity (sprinting), or muscle contractile velocity an athlete is able to produce through a specific movement. This training zone is typically classified by using intensities of approximately < 30% of 1RM

What are you or your athletes training for?

What training effects are you trying to elicit?

These factors will determine the loads that you prescribe.

Train smart,

Joe

References

Allerheiligen, W. B. (1994). Speed Development and Plyometric Training. In Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, ed. T. R. Beachle. Human Kinetics. Champaign, IL.

Kent, M. (2012). The Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science and Medicine. Oxford University Press. Croydon. UK.

Kurz, T. (2001). Science of Sports Training. How to Plan and Control Training for Peak Performance. Stadion. Island Pond, VT. USA.

Tidow, G. (1990). Aspects of strength training in athletics. New Studies in Athletics. 5(1).

Williams, T. D., Tolusso, D. V., Fedewa, M. V., & Esco, M.R. (2017). Comparison of Periodized and Non-Periodized Resistance Training on Maximal Strength: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine. 47(10).

Verkhoshansky, V., & Verkhoshansky, N. (2011). Special Strength Training Manual for Coaches. Rome. Italy.

Zatsiorsky, V. M., & Kraemer W. J. (2006). Science and Practice of Strength Training. Human Kinetics. Champaign, IL. USA.

Comments